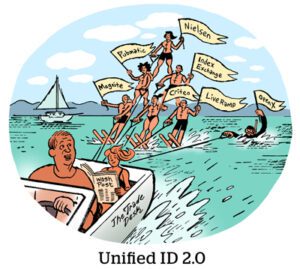

Programmatic auctions are creating so many carbon copies of themselves, it’s threatening to topple the entire structure of programmatic.

The bid duplication is getting so extreme, buyers are starting to take notice of this strange behavior.

Instead of seeing the whole universe of bid opportunities, demand-side platforms see only a small portion of inventory copied many times, which impairs their ability to scale campaigns.

Their attempt to solve the problem – using a method known as traffic shaping to process fewer bid requests to create a clean path – only ends up culling valuable bid requests in the process.

The issues caused by bid duplication are no secret. But, as is often the case in ad tech, being proactive is a disadvantage. Any single publisher attempting to fix the issue on their own will experience a decrease in revenue so profound that changing alone isn’t an option. Meanwhile, removing waste from bid duplication could squeeze SSPs, who each get a chance to sell everything under the current setup.

Yet many in the ad industry want bid duplication to stop. But first, more people need to understand what they are seeing.

The simple complexity of bid duplication

Buyers tend to assume programmatic works logically and rationally. A publisher pings SSPs, which gather bids from DSPs for the ad slot. The buyer with the highest bid wins.

What really happens is laughably more complex. When bid requests go out through different SSPs, they are indistinguishable from each other – despite the existence of an ID to address this issue. Buyers sift through dozens of duplicate bid requests, unable to tell the difference between them. Twenty bid requests from an SSP for one ad may look identical to 20 SSP bids for 20 different ads.

Bid duplication has been on the rise in lockstep with header bidding, which is the standard way large publishers set up their programmatic ad stack. Now that header bidding has become the default, publishers ping all their SSP partners for any ad availability, asking them to return a bid.

But DSPs have been unable to counter-adapt. It’s like they’re walking down a grocery-store aisle, and every can of soup they see is exactly the same.

Here’s an example of how noisy it is out there: PubMatic boasted of processing 56 trillion impressions in Q3 2022, up 33% from the year before, which averages out to 7,000 ads for every person on the face of the Earth. The only way that number makes any sense is as the result of massive bid duplication, which benefits no one (probably not even PubMatic, at least in the long term).

PubMatic told AdExchanger there are even more bids it doesn’t process. “We regularly reject impressions that don’t meet our inventory quality standards or that we don’t believe we can effectively monetize,” a spokesperson said.

Here’s another scenario: If an SSP sends a DSP 100 bid requests for a publisher, it would be logical to assume the requests are for 100 different ad spots. Incorrect. “One issue we’ve encountered is that [SSPs] send 30% of the publisher’s traffic – the stuff they think is best – and they send it three times,” said Will Doherty, VP of inventory development at The Trade Desk.

Sending more than one bid request for the same ad impression is a no-no among most DSPs, including The Trade Desk and Google DV360. But that just means some SSPs try to sneak around or justify their actions as yield optimization (FreeWheel was recently caught for a plan to send multiple bid requests for the same inventory, a tactic it euphemistically referred to as “Smart Bidding.” )

These types of auction shenanigans “are the exact reason DSPs won’t explain or make public why they make filtration decisions,” said Sonja Kristiansen, chief business officer at TripleLift.

Traffic shaping: The medicine that makes things worse

To combat bid duplication, DSPs have turned to traffic shaping, a technique that filters excess bids using a combination of algorithms and manual selection to curate the inventory that buyers evaluate.

But the process doesn’t actually deduplicate impressions for DSPs, and, paradoxically, the guesses made during traffic shaping can exacerbate the negative effects of duplication.

Rather than curing the disease, it treats a symptom.

Processing billions of bid requests is expensive. In the face of skyrocketing cloud bills, SSPs and DSPs alike have implemented traffic-shaping tech as a cost-savings measure. Magnite, for instance, bought nToggle for traffic shaping back in 2017.

In practice, a DSP might tell an SSP to give it 6 million QPS [queries per second], after which the SSP will try to send the DSP its “best” stuff, as in the inventory the SSP thinks likeliest to win given the constraints.

For example, Microsoft Advertising’s SSP offers its DSP partners a self-service tool they can use to say what supply they want, such as CTV inventory, banner inventory or specific domains. Microsoft also uses data science to reject ad requests that aren’t formed correctly or have missing data.

Traffic-shaping algorithms rely on historical data about what inventory has been bid on in the past to determine what to send buyers in the future. The danger in this approach is that buyers end up seeing an increasingly narrow view of what’s out there, losing the chance to discover new inventory.

“What winds up happening,” said Chris Kane, founder of Jounce Media, “is that every exchange chooses the same impression” because they’re basing their decisions on the expected revenue for each impression.

DSPs shape traffic, too. Even if a DSP professes to listen to a bid request, it may not process it. Many DSPs and SSPs use their own filtering criteria and algorithms to throw out impressions before they get to buyers, an efficiency play that saves money.

Manage that QPS

Traffic shaping exists because it’s too expensive to process all the duplicate ad requests, which are measured in millions of queries per second (QPS). The total amount of impressions out there is growing as web traffic grows, but the number of requests for those impressions has grown exponentially.

“I look at it like inflation,” Doherty said. “They are just printing more and more impressions. In a market where supply already outstrips demand by a significant magnitude, they are creating more supply and reducing and diluting value.”

As buyers and sellers sift through more (and more) duplicate impressions, they run up higher server bills to buy the same amount of ad inventory. You could call this a sustainability issue, or you could call it a margin issue. Either way, operating expenses, to use CFO jargon, are spiraling.

When a smaller DSP asks an SSP to limit the QPS it sends, it’s being pragmatic about what it wants to buy, but it’s also about the DSP needing to maintain margin – particularly because cloud servers are usually one of the top costs for a DSP or SSP.

When EMX went bankrupt a year ago, the SSP owed $900,000 to cloud provider Amazon Web Services, which requires monthly payments – and that was when its business was near death. The Trade Desk spent $264 million on platform operations during the first nine months of 2023, or $730,000 per day, a figure that includes everything involved in running a DSP, including paying server bills to Amazon Web Services and Databricks.

“With header bidding, the operating costs of the platform have increased materially,” said Alex Chatfield, head of Microsoft and Netflix ad sales for Microsoft Advertising, which operates both a DSP and an SSP as part of its Xandr acquisition.

Now that most of ad tech uses cloud servers instead of maintaining their own servers, they have the ability to dial QPS up or down depending on how business is going. A company may entertain more QPS during big advertising moments, such as Black Friday, or reel it in to manage costs.

Bid duplication is harming buyers

When bid duplication is combined with traffic-shaping tech, the addition and subtraction end up removing valuable inventory. Buyers find it too hard to scale with anything deemed a niche site, including minority-owned publishers.

While many brands have made commitments to spending with diverse-owned media companies, multiple buyers confirmed that traffic to these sites is disproportionately filtered out by traffic-shaping tech.

Minority-owned publishers and content providers get filtered out because they often don’t generate enough bid volume or are forced to use multiple technology connections to allow their inventory to be available programmatically, said Emily Kennedy, SVP of programmatic partnerships at Dentsu Media US.

AdExchanger brought up the negative effect of filtering tech on minority publishers in conversation with numerous industry experts, many of whom had never heard of this issue – or couldn’t visualize how technology could lead to this type of response.

But the problem extends beyond just minority-owned publishers. An auto insurer looking to buy on niche sites that reach car shoppers, for example, could find it impossible to scale if the so-called “medium to low value” users on that site are filtered out.

“DSPs make a lot of network-level decisions that don’t always align” with what a marketer might need, noted Lara Koenig, global head of product at media buying agency MiQ. For CPG marketers, auto brands or advertisers that run on a lot of mobile gaming, she said, “having a one-size-fits-all supply strategy on the DSP side won’t work.”

In other words, what a niche buyer uniquely needs can be perceived as “too unique” and filtered out before that buyer even has a chance to raise their hand and say they want it.

And good luck to any brand that wants to curate inventory even further: “If I want to serve on this very specific [publisher] brand and specific DMAs and add on brand safety elements, it can be challenging,” Dentsu’s Kennedy confirmed.

Troubleshooting scale issues is a headache, since duplication and filtering happen every step of the way.

For example, if inventory is being filtered out before it reaches a buyer, is that because the publisher didn’t sell a piece of inventory through an SSP or because the SSP was sending over less inventory to meet a DSP’s QPS caps? Or maybe the DSP simply filtered out the impressions.

Bypassing traffic-shaping and filtering algorithms altogether is often the only solution. When buyers switch to programmatic guaranteed or private marketplaces, they can usually sidestep the technology that’s removing inventory they want to buy.

The reason this approach works is because it bypasses the “underlying algorithms that cause favoritism,” Koenig said.

Still, buyers suspect the very existence of bid duplication and traffic filtering serves to raise CPMs.

“You are recycling the same stuff – and paying more for it because the pool is smaller,” Kennedy said.

Can the bid duplication ever stop?

The more bidders in an auction, the higher the revenue. Bid duplication persists because publishers and SSPs will experience a revenue hit if they stop, and DSPs can’t reprogram their algorithms to avoid penalizing sellers.

Let’s put a spotlight on DSP algorithms for a moment.

Publishers and SSPs have discovered that DSPs have a volume bias. Many DSPs assume a publisher with more ad impressions for sale – 30 million, say – is larger and more valuable than a publisher with 10 million bid requests, even if both in fact only have 3 million ad slots for sale.

Part of that bias derives from how DSPs pace campaigns.

If a DSP receives 12 bids for a single impression, it might return 12 bids – and the publisher can choose the highest one instead of accepting a single bid. Sending more impressions tends to squeeze out more bids, giving SSPs higher options to choose from.

These auction economics are hard to change, and until DSPs can figure out how to remove the volume bias in their algorithms, bid duplication will continue.

“Believe the bidder, not the DSP,” TripleLift’s Kristiansen said.

DSPs might say they want quality, for example, but if they direct their bidder to gobble up cheap inventory, don’t listen to what they say; look at what’s going into their mouth.

If DSPs really want to discourage duplication, their bidders should stop rewarding volume.

But changes in algorithms alone will not fix this problem. Policy changes need to happen, too.

Algos & policy

Of the two largest DSPs, The Trade Desk has been most vocal on the policy front. It wants SSPs to start using its Global Placement IDs (GPIDs), which would help deduplicate impressions. OpenRTB specs also contain a transaction ID that DSPs can nudge SSPs to use.

But three years in, it’s unclear how many exchanges and publishers are following The Trade Desk’s instructions.

More recently, the independent DSP also made a move to disregard floor prices, a move designed to disincentivize SSPs and publishers from sending out the same impression at different floor prices.

In reaction to initiatives designed to address duplicated inventory, “publishers have a right to be worried,” notes Microsoft’s Chatfield.

“If it’s done universally, it should have absolutely no impact since there is the same amount of real supply – it just has to have mass adoption,” he said. “It becomes a game theory problem, where first movers get penalized.”

The Trade Desk is aware of that disadvantage, which is why it wants to encourage publishers to adopt its new policies. “A couple ways you can reward publishers doing the right thing are listening to more traffic when publishers give you more access to it, and considering their traffic more often,” Doherty said.

To cover its bases, The Trade Desk developed OpenPath, a direct connection to publishers that gives it a baseline of deduplicated inventory and data it can apply to ensure SSPs give it the cleanest possible supply path.

“What OpenPath gives us is clarity,” said Doherty. Since it’s not duplicated or traffic shaped, it can use OpenPath to “judge the efficacy of all other paths.”

Where’s Google?

In contrast to The Trade Desk, Google has been absent on the policy front regarding bid duplication.

With an antitrust trial looming this spring, which will specifically address its inflexible tech setup – you know, the one that caused the ad tech industry to develop header bidding and bid duplication in the first place – Google is unlikely to touch anything that could cause publisher blowback.

“We are walking a tightrope where we want publishers to support monetization that best supports their goals,” said Dan Taylor, VP of global ads at Google.

If Google did anything, it would have to be under the auspices of an industry org. “I do think it would be helpful to get to an industry dialogue around what are the right practices here,” Taylor said. “Right now, I don’t think there is an active dialogue.”

Addressing bid duplication could fall under the purview of an industry org.

“We need industry standards, and The Trade Desk is the closest we’ve come to setting those, albeit aligned with their own goals,” said Kristiansen, referring to its GPID (global placement ID) requirement. “It almost needs to be at the IAB level.”

2024: The beginning of the end for bid duplication?

The jury-rigged nature of programmatic in the current market bothers many in ad tech. It’s inelegant and it’s not sustainable – either structurally or environmentally.

“Mature markets don’t have that inefficiency or waste,” The Trade Desk’s Doherty said.

But the industry is still not coordinated on how to address the problem of bid duplication. “This is an enormous industry dynamic that not enough people are wrapping their heads around,” Kane said.

But change is possible. Programmatic has altered its fundamental mechanics before.

Header bidding usurped the waterfall setup. First-price auctions replaced second-price auctions.

Now, buyers need a solution to defragment the auctions taking place across dozens of SSPs for the same ad spot in a way that combines policy and algorithm changes.

The challenge will be implementing this solution in a way that makes the problem better – not worse.